Who are you? What makes you you? Is it the precise material configuration of atoms that comprise your physical being? A pattern of neural activation? Your absurdly good sense of humor, or your unrivaled good looks?

Probably many of these things and more. It probably involves some ship of Theseus-style principle of continuity. Probably some “more than the sum of its parts” action, right? Perhaps a little je ne sais quoi? But there’s some central “there” there, some essence, no? Maybe it can’t be distilled down to anything. Maybe it can? Maybe that’s what we call a soul.

Can AI capture soul? Can AI capture your soul? The coming age of AI predominance will increasingly confront us with these and a cluster of similar questions around them. Who are you? Can AI capture that? Can identity be virtualized? Should it be?

Embeddings, a core feature of almost all contemporary AI models, serve as a potent symbol of and entry point into understanding why these models provoke such questions. So what are embeddings? A good high level description, I think, is that they’re a way of representing concepts and the relationships between them through numbers. The second part of that—representing not just concepts, but the relationships between them—is critical, because it means that they can interact with one another. Things only mean things in relation to one another, and AI’s power is in its capacity to grasp and produce meaning—to structure relations between things. It’s super easy to represent concepts alone through numbers, and if embeddings did only this they would basically be useless. You can arbitrarily assign meanings like house = 1, camel = 2, gourd = 3, ad infinitum—a number for every concept! But this encoding system doesn’t capture the relationships between concepts. Two houses do not a camel make.

Embeddings change this, creating a mathematical system of relations between concepts. They’re formed when an AI model is trained. You can think of a model as a kind of tiny universe of meaning, where more similar things are closer to one another in a very high-dimensional (“hyperdimensional”) space. Concepts gain meaning through their embeddedness in this shared abstract space, referred to as latent space. A model contains a coordinate system that maps concepts and their semantic proximity in latent space. Per the classic example, take the coordinates for king, subtract man, add woman, and you arrive at (roughly) the coordinates for queen. These coordinates are what we mean by embeddings.

Their significance, then, is no less than the invention of a semantic geometry. Through embeddings, we’ve bridged the numerical and the semantic, the quantitative and the qualitative, creating a fluid yet systematic field of meaning through numbers. That duality forms the basis for the paradigm of generative media—organic, cogent text and images, produced by massive clusterfucks of digits.

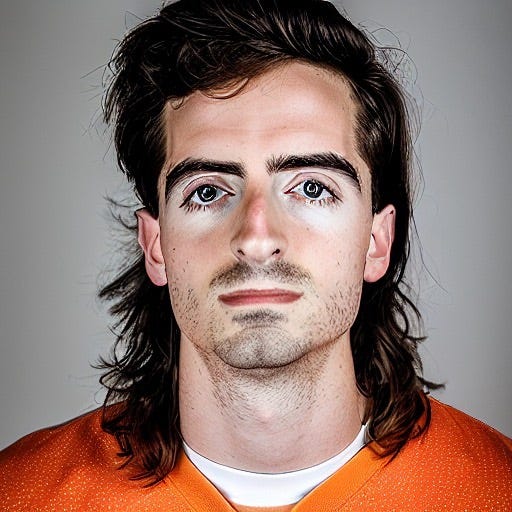

Enter Hyperportrait I. Hyperportrait I (“one”) is a self portrait by way of embedding. What does that mean? As we said earlier, an embedding is a numerical representation of a concept held by a model. The concept preserves its meaning because the model captures its relationship to the rest of reality. Hyperportrait I was made by training a model on images of me such that it develops an internal visual representation of who I am. That representation is my embedding, and that embedding, extracted from the model, is what you’re seeing in this piece.1 As art dealer extraordinaire Sofia Garcia pithily described it, it’s a “self portrait in latent space.” It’s a portrait of the abstract idea of me.

For the first time ever, we have a way of meaningfully representing that idea, or any idea, in a rich and usable yet concise form. Again, this is the novelty of generative AI. There’s an argument to be made that an embedding is the most potent form of abstraction ever produced. It’s not an encoding for a bunch of photos of me. It’s a learned representation, like the abstract idea you have of someone in your head. It gets activated in specific ways when you picture them in various contexts, and each of those reimaginings is made possible by the fact that you have a robust, multifaceted understanding of what they look like that transcends any static image.

So too with generative AI. The embedding in Hyperportrait I can be re-injected into a model and used to make all kinds of images of me. It can depict me rocking a mustache, as an emperor in a Roman marble bust, in the style of a Van Gogh painting, or in a ménage à trois with myself (try it out!). It is, in essence, a portrait that contains all other portraits.

Plato hypothesized the existence of a realm of pure ideas called the “Forms”, from which all things in our perceivable reality derive.2 Any given chair you see is a specific, and thereby limited, manifestation of the abstract Form of the chair. Embeddings can be thought of as a kind of technologically-mediated Platonic Forms, the pure idea of the concept they represent, from which any specific generated depiction is born. Hyperportrait I, by this metaphor, is a “Platonic portrait.”

There is in these numbers, then, a me that’s more me than any lone painting or photo could ever capture. They present the embedding as the pinnacle of modernist abstraction. It’s an evolution in the tradition of Cubist and Futurist ideas around depicting subjects in time; of Kandinsky’s and Malevich’s ventures beyond the realm of representation; of whatever bullshit Duchamp was on; of Yves Klein’s efforts to conjure the immaterial; and of Bernar Venet’s mathematical diagrams, which sought to bring the language of pure scientific abstraction into art.

However, where so many of these artists and their works championed abstraction as a freedom from representation, an end to be pursued for its own sake, Hyperportrait I takes a position of skepticism. Information technology and modern art have shared over the last century in the pursuit of ever-greater abstraction, and it’s worth asking for a moment toward what end. Hyperportrait I is thus intended to demand meditation on the abstraction itself. There’s a dissonance formed by the juxtaposition of this abstraction, a giant heap of numbers, with its subject, a flesh-and-blood human being.3 A person, to us, is the polar opposite of an abstraction. So what kind of future does it portend when we give technology the keys to abstraction of the human? Not just the visual image of humans either, but our psychic likeness. LLMs produce an abstraction of cognition itself. From here, the abstraction of identity is mere steps away.

Ironically, this probably all sounds very abstract. Who cares if “the abstraction of identity is mere steps away”? What does that even mean? What it means in practice, or at least threatens, is that as our cognition becomes abstracted away, our jobs go with it. As our creativity becomes abstracted away, our artistic pursuits go with it. As our personality becomes abstracted away, our relationships go with it. In each instance we stand to be replaced by artificial entities that can (seemingly) perform our function and serve our needs better than any “mere” human ever could. When you successfully abstract something, you gain the ability to replace the original with the abstraction. We abstract everything around us away until we ourselves end up washed away by the process. Maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe we’ll live better lives when everything we interface with is a tamed abstraction tailored to our needs. My guess is that we won’t. Every abstraction is by definition lossy. The map is not the territory.

Is abstraction bad, then? The question feels leading because it runs counter to an implicit teleology embedded in modern society (onward, abstraction!), but I’m genuinely not sure of the answer. The hope with this work isn’t to convince, but to pull the viewer into a wrestling match with some questions that bear asking. What is abstraction for? How does it serve us, in technology and art? Does it foster a good life—material, social, and psychological? Who am I, if these numbers can meaningfully capture my essence? Who are you?

Hyperportrait I is the first in a very limited series of these portraits. For inquiries around commissioning a hyperportrait, please reach out via email at ktesherick@gmail.com or DM on X/Twitter.

A brief formal primer: the brackets denote that this is a tensor, a term for an n-dimensional vector in machine learning, similar to matrices in math or arrays in non-ML programming. The underscores beneath many of the digits signify negative numbers. This allowed the numbers to fit into orderly rows, which was important for maintaining the abstract sterility of the piece, so at odds with its human subject.

There's considerable debate among Platonic scholars about what exactly Plato meant by the Forms and for what kinds of concepts they exist. I'm embracing a looser interpretation here, but also I'm not all that interested in what the correct interpretation of Plato's writings is. What matters is that there's a philosophical idea worth considering that the entities of our reality are manifestations derived from some ideal realm.

I first started thinking about this piece in 2023, but had only the vague semblance of an idea in the form of a tagline floating around in my head: “embedding as artwork”. The path from there to the hyperportraits seems obvious in hindsight, but at the time I wasn’t at all sure what that would look like. Then in early 2024, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst released a piece called Readyweight θ. It was a pure, clean expression of the idea: embedding as artwork. My initial response was “Shit, they did it.” But my thinking quickly turned to where else the idea might be taken, and what I, personally, wanted to communicate around it. My fixation veered toward the nature of the abstraction itself and what this spells for the human person, and confronting the viewer with these concerns.

So this answers the question I posed to you, that you can pull out of the piece pictures of yourself. Very cool.