Manglecore and the Aesthetic of Strangeness

On AI, weird art, and the world they reflect

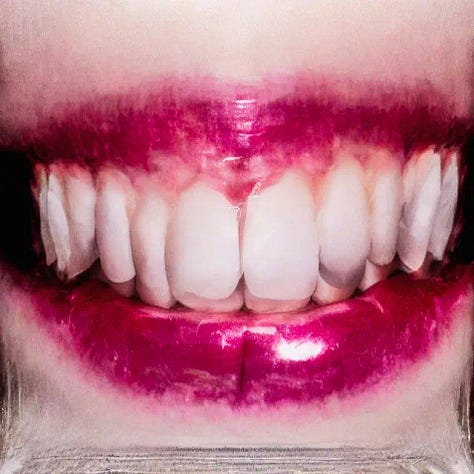

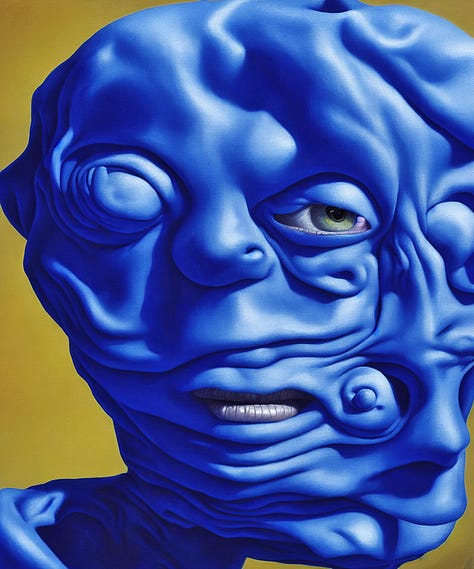

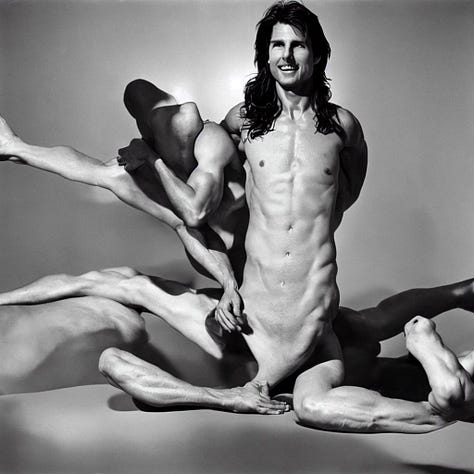

There’s an aesthetic that has come into vogue in AI art over the last couple years that I’m going to call “manglecore.”12 As the name suggests, it looks at the mangled distortions of faulty AI image generator outputs and embraces them. Anyone who has been online and involved with tech or art of late will likely know the look I’m referring to. It appears particularly among human subjects. Botched faces. Tangled limbs. Hands sprouting seven fingers, some of which appear to be melting. Unevenly spaced and off center eyes covered in a glaucomic glaze. Folds of skin curiously resembling fucked up genitals. And the teeth! Jagged, monstrous, almost shark-like teeth, doubling up in overlapping rows. It’s the unmistakable appearance of a human, but with something gone seriously wrong. If you squint, it almost looks alright.

Yet despite the borderline-repulsiveness of the manglecore image, it has come into an artistic vogue alongside this new technology and medium. With the rise of any medium of expression comes the birth of a vogue, or set of vogues, and in this case, two styles in particular have risen to prominence on the cultural stage. The first, and in some sense primary, style is what I will refer to as the “Midjourney aesthetic.” The Midjourney aesthetic, whose name derives from a popular model known for its uber-sleek outputs, is that look of impossible polish that renders an image almost more than real, like CGI, a hyperreal synthesis of detail that could only ever exist as image, never flesh and blood.3 It’s like that guy that’s so handsome he looks fake, Huxley’s “Brave New World” in visual form. That’s the essence of the Midjourney aesthetic. It’s pretty, it’s alluring, it’s cool, but it doesn’t bleed.

This aesthetic has its value. It’s compelling in its pragmatism. It checks all the boxes, does what we tell it to, can be put toward an end. It’s useful. But it doesn’t make for great art. It doesn’t “disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed,” doesn’t move us, doesn’t instruct, doesn’t enlighten, doesn’t even really show us what’s possible. It’s crucial here to distinguish between the aesthetic typically produced by the technology and the technology itself. The tech is the image model, which can produce all sorts of looks, Midjourney aesthetic and manglecore alike. However, when left to its own devices and working well, it gravitates toward the former. The medium isn’t quite the message, but it is a possibility space, and thus a probability cloud, of all that the message might be.4 Gases take the shape of their container, and the message will conform to the affordances of its medium. The Midjourney style has become the aesthetica franca of the image model, and it’s a practical one—inoffensive, adding dollops of visual flair, filling in details the prompter wasn’t able to or didn’t bother to think up, smoothing things out. But precisely on account of this pragmatism, it has no artistic merit of its own.

There’s a case to be made that this kind of smoothing is unhealthy in the same way that Instagram posturing, Snapchat filters, Photoshop blemish reduction and body enhancement, and overrepresentation of certain body types in porn are unhealthy, encouraging distorted self-perception and doing some serious psychic harm in the long run; and that for this to soon be the predominant mode of image production in our society is deeply troubling. The world will never look like what the Midjourney aesthetic suggests, but it subtly seduces us into believing that it can. It’s grotesque in its perfection, which threatens us with further alienation from ourselves. Its purity sells us lies about who we are or could be. Even the manicured facades we construct on Instagram feel dull and lifeless in comparison. It says “I’ll see your overdone vignette and raise you an impossibly dramatic bokeh.” In this sense it’s actually a fitting product of and for the culture of image that we inhabit, where, in a Baudrillardian (or Debordian) flip, the flattened images we see on the screen have become the primary reality, sign turns to simulacrum.5 The flattening is pragmatic—it’s easier to manage. It renders the world into matrices and bitmaps, contained and manipulable vectors. Yet what it gains in efficiency, it loses in heft. Mere image is the foundation of a weightless world.6

I’m not sure how seriously to take these (my own) complaints. On the one hand, they’re just pretty pictures dude—relax. On the other, a good bit of research over the last several years has implicated platforms like Instagram, which cultivate a culture of image manufacturing that gives rise to impossible standards for beauty and quality of life, as being really, really bad for mental health, especially that of young women and girls. Some of the greatest dangers we encounter are incredibly banal. In fact, it’s precisely because of their banality that they’re so pernicious—they appear of little harm, and so we dismiss them.7 This is enough to give me pause.

But all of these moralistic concerns are an aside (not because they’re irrelevant, they’re just not the focus of this essay)—the Midjourney aesthetic is still just artistically boring. GPT-speak is its linguistic analogue, with its sanitized, flavorless, peppy corporate-speak. Together they are the face and voice of an existence optimized for KPIs and customer retention, and lip-service holistic wellness while we’re at it. They challenge no one, say nothing daring or new, and offer only shallow comforts.8

Manglecore is the antithesis of the Midjourney aesthetic. It is its ugly twin born of the same technological womb, yet popular in its own right. The Midjourney aesthetic assumes the image model’s status as tool, takes it, and runs with it, using it practically, for what it’s good at. Manglecore, by contrast, sits with the tool and examines it. This dichotomy explains manglecore’s prominence, especially among artists. Artists naturally position themselves counter to the mainstream, commonly with an anti-pragmatic ethos, but in doing so establish a vogue of their own. Often this “schismogenesis” involves questioning that which most have taken for granted.9 The bulk of output, art or otherwise, flooding from AI image generators right now is of the Midjourney variety. Manglecore art, by turning an eye toward the imperfections of the technology—the gnarled limbs and deformed faces it spews out—calls attention to the tool itself and invites the viewer in on this act of examination. It makes us ask, “What the hell am I looking at?”

But it’s not the mere fact of their shortcomings that make these images interesting. Simple blank screens rendered in error would be much less compelling than pictures of people who look like they were reared in radioactive goo. It’s the fact that where these models fail, they often fail quite weirdly, and in ways that lend broader insight into the world we live in. These failings comprise a set of “anti-virtues”, qualities rendering them useless for practical purposes but all the more valuable for artistic ends.

Among their anti-virtues is the way they conjure nonsense that appears as if it’s verging on sense. It’s horrific in its proximity to reality, almost there yet so alienly far away. In this way it can serve as a reminder of the beauty and exquisite calibration of humanity as a species and our world more broadly.10 So much had/has to go right for all of this to exist in the way it does. There also may be some solace here. Take one look at these ghoulish creations and grant yourself a moment to gloat over AI, to relish your superiority, to feel a smug gratitude for the elegant, balanced hand by which nature composed you.11 Say to yourself, “At least I’m not that big of a freak.” Where the Midjourney aesthetic whispers that you’re not good enough, the manglecore chokes out “GRANK oggnub hicjjtth!!”, and you know that you’re alright.

And yet while its literal appearance struggles to approximate resemblance to our world, the essence of the manglecore image aptly captures the spirit of our time in its own way through its abject bizarreness. With garbled language and mangled faces, the outputs of the image model manage to portray the discomforting, inexplicable strangeness of life in the modern age. The frenetic, dissociative, even Lynchian peculiarity of a collection like Frank Manzano’s Current Value (see video below) seems a lot less out there after a couple hours spent scrolling through TikTok or reading the latest news out of Florida.1213 Reality bends itself into new and unexpected shapes every day, re-forming our expectations of it, of people, of life. It’s a contortionist with broken pain receptors and unlimited access to CRISPR, capable of twisting itself in ways we never thought humanly possible. We live in a weird world, and it’s getting weirder by the day. The manglecore image gestures at that.

The reasons for this escalating strangeness, I think, are several fold. Perhaps most obvious is the accelerating pace of change. Change brings with it the new, and the new is by default foreign to us for a time.14 Thanks to developments in communication technologies like the internet, this rapid pace of change, both cultural and technological, is then amplified and put on display for the world to see. And in an online economy designed for attention capture, weird wins out (“Ice cream so good!”). This creates a cascade of strangeness hypervisibility, where technological and cultural development broadens the range of what can happen, anything that can happen will happen, anything strange that happens will be shared online, and anything strange successfully propagated online will induce a mimetic (and memetic) absorption and replication response. And so on.

Also fundamental to the strangeness of modernity is the strangeness of rules and systems. There’s a particular kind of weirdness that arises when you put large systems into place with the touch of a human hand that then pulls away. As the activity of these systems gets further and further from the hand that set them into motion, they come to carry its imprint less and less, and weird (from a human vantage point, though perfectly normal according to the system’s design) shit begins to happen. Bureaucracy is an example of this phenomenon at the level of human organization, your Twitter feed embodies it algorithmically, and neural networks now manifest it anew. All, in their own way, are black boxes, and all reflect that blend of absurd, surreal, and mundane that today we refer to as “Kafka-esque.” Kafka, in his treatment of early 20th century life, was a prescient seer of the world that this “systems weirdness” would occasion. The predicaments that characters like Gregor Samsa and Josef K. find themselves in hit us just as forcefully today, perhaps even more so, in their comically eerie inexplicability. Yet where this feeling was ambient in the era of Kafka, a percolating ether bubbling up from the nascent wellspring of industrial modernity, it’s now everywhere, everything. The world confronts you with the bizarre. The only place where this is truer than in New York City, where I live, is on the internet, where we all live. Estrangement is an inevitability of such a reality. We are becoming viscerally strange to ourselves, even as, through advancements in the likes of genomics and neuroscience, we come to “know” ourselves better and better. Literal alien-ation consumes the zeitgeist—we know more about the prospects of life on Mars than we do about the lives of our own neighbors. Manglecore and other aesthetic genres similarly preoccupied with strangeness offer one means by which we might confront the lurid freakishness of these facts, especially insofar as they leverage these very strangeness-producing systems (like AI) to illustrate their point.15

The above reasons all champion this genre on account of its aptness in echoing the cultural zeitgeist. It also manages this task on technological grounds, working with tech whose surface level flaws are very “of this moment” but whose core essence and challenges (i.e. the inherent properties of generative AI) will shape our world for decades to come. In that way, AI art of today holds a position similar to computer art in the 60s and 70s. Right now manglecore artworks do something that only the image model can. The deformities are so strange as to almost be unachievable by human hands. It’s truly a distinctive aesthetic of its own, a wholly new dream brought to us by the flawed miracle of diffusion. Yet soon all that image models will be able to do is everything that has been done already. What I mean by this is that in its developed form, the image model just works, faithfully synthesizing its knowledge of the non-deformed images it’s been trained on to produce the images we ask for, sans mangling. There are no more accidents. In fact with the latest models we’ve largely already arrived here. The imperfect outputs are no longer inescapable and in fact take deliberate work. “Perfect” images don’t require the craftsmanship they did even just a year ago. Manglecore is now a choice, not a hurdle. For a moment the image model was a new medium, its own thing, rather than a sanitized retreading of all that had come before. With this moment just freshly in our wake, the force of its aesthetic remains worth working with and dwelling on.

The composite of these facets of manglecore points to a meta-virtue, one which these anti-virtues are all in service to: manglecore is an art of this era, rather than one merely from it. This is a distinction that runs through much of good art. Art from a given era is a product of the realities of the time yet doesn’t meaningfully call attention to and consider them. It doesn’t see the water that it’s swimming in. It says “I was here” without being able to really say what “here” was like in a language universally human enough to resonate across past, present, and future.

Art of an era, by contrast, transcends this myopia. It is “of” it both in that it’s from it, but crucially also in that it’s about it, and straddles this duality deftly. It steps back from the reality in which it’s situated to view it at a distance, to see the bigger picture. But it can also then zoom back in to capture the specific details of people, places, and moments that give impactful art its color, character, and force, and interweaves threads of the bigger picture through those details. It is self-conscious of the age, in dialogue with it, able to see it as both self and stranger. Warhol, more than any other artist I can think of, was a master of this. He captured his time in flashes of lightning, catalyzing pervasive realities in the ether of his age into material realities in precise and electrifying ways. In the likes of Marilyn, Jackie, and Campbell’s, he found symbols undeniably of that moment yet which speak to us even now. Picasso too, alongside Braque and their fellow Cubists, evoked a world that was coming to see itself in a radically different light. Guernica, his mural depicting the WWII-era German bombing of the Spanish village of the same name, deftly exemplifies this process, the disjuncture and torment of its figures reflecting the horror, dissociation, and disfigurement that the modern world had wrought. Though a work of similar weight has yet to be added to the manglecore canon, the genre embodies obvious stylistic parallels to Guernica, its own aesthetic of deformity offering opportunities to visualize corresponding sentiments in the present day—alienation, estrangement, dehumanization, and the ubiquity of the bizarre. Manglecore’s absurdity renders it capable of humor too, which is potent, but a subject for another day. Through all of these means, manglecore makes for an art of our time, embedded in yet speaking to it. It’s a fitting mode of expression for a world deeply steeped in strangeness, where life so often feels like a perpetual fever dream.

GANs have been around for a decade, diffusion models have been massively popular since 2022, and the technical constraints that originally spawned the manglecore look have largely been surpassed, yet still we dwell with the fascinating distortions that image models yield. They linger with us. So what now? What I’ve called manglecore has only just begun to come into its own as a genre of art. It’s enough of a “thing” that some significant number of artists are working with it, yet it’s still well shy of being overdone. There’s more to be done with it, plenty that the genre is capable of expressing that remains unsaid. The great works of manglecore are yet to come. It’s also not the only way of producing great art with image models, or making work that speaks to the strangeness of our day. Especially if you can get under the hood and tinker with them, these models are uniquely adept at producing strangeness.16 They offer the vast territory of latent space at our fingertips, and we have nearly all of it left to explore. There’s an ancient Chinese curse (probably apocryphal) that goes, “May you live interesting times.” Call us cursed if you will, but we undeniably live in interesting times. May we put them to good use.

“Deformalism” was another name contender. If you like this better then go ahead and run with it. It’s more academic-ese, but also features a fun lil pun that pokes at its own academicism. I also considered calling it "warpcore," which sounds a lot liked Warped Tour, but "mangle" felt most true to the work. “Manglecore” is itself a manglecore name, kind of vulgar and hideous-sounding in its own right.

Manglecore also happily sounds not too far off from “manticore” a mutant beast of Persian mythological lore melding the head of a man, the body of a lion, and the tail of a dragon (or scorpion) all into one. The manticore's freakish nature is a nice complement to the Frankensteinian nature of AI's jumbled creations, the imagination of our AI overlords now supplanting that of old Dr. Frankenstein.

This technically is CGI—computer-generated imagery—but you know what I mean.

French philosophers Baudrillard and Debord both wrote about the process of society coming to engage with itself at the level of appearances rather than of essences, using their respective terms “simulacrum” and “spectacle” to refer (roughly) to the flattened images that our symbols get reduced to.

I think TikTok and Reels are in some way a return to “the real”, or a reapproximation of it. The problem with them then is that they just become a more seducing means of ignoring our own reality. They feel richer, more whole, more satiating. They’re still not reality.

Hannah Arendt famously wrote about “the banality of evil” in the context of World War II.

This is not an all out condemnation of work made in this aesthetic vein. Worthwhile things can be done with it, but the aesthetic per se is a vapid one.

Anthropologist Gregory Bateson coined the term schismogenesis, which I'm adapting slightly here, to refer to the process wherein two groups in close proximity develop their identities in opposition to one another. The example of artists is somewhat different: artists push away, establishing the cultural cutting edge, society (often) chases. In this way it’s more like a toxic relationship between two people with different attachment styles.

This made me think of William Paley the 18th century philosopher who saw this exquisite calibration as evidence of an intelligent designer behind our existence, like a complex watch one might find on the ground and assume the existence of a creator behind.

It won’t last long.

“Lynchian” i.e. resembling the work of David Lynch. Film and TV director of surrealist classics like Twin Peaks.

No shade at Florida, y'all just always seem to have a lot going on.

In the words of one of the great philosophers of the 20th century, "The times they are a-changin!"

I think they're particularly well-equipped to take on themes of dehumanization in compelling ways that I haven’t seen given a serious effort yet.

You can do said tinkering by using open source models, away from the stifling control of the likes of DALL-E. The Stable Diffusion (model) + Automatic1111 (GUI) combo is a good place to start.

Fantastic essay thanks

Excellent assessment. Really enjoyed reading this.